Dona Rosa was born in the early 1900 and died in the 1980s. She, like many Oaxacans, made pots and sold them at market for her living. Then plastics came. Mexicans fell in love with the bright colors, lightness, and cheapness of plastic and stopped buying the pottery. The Mexicans and Zapotecs who depended on selling pottery for a living were in dire straights, not to mention the danger of the art of making it being lost.

Rosa signed the pottery pieces she made by rubbing the pattern of a rose into it using a piece of quartz. One day she mistakenly rubbed a whole pot, and then only left it in the kiln 6 to 8 hours instead of the customary 12 to 14. The pot came out a beautiful shiny black, instead of the dusty grey they normally were, but it was useless because it wasn’t cured enough to hold water.

She stuck it off to the side until a tourist noticed it and insisted on buying it, though Rosa protested because it was worthless. That was the beginning of the Oaxacan Black Pottery as we know it today, and the saving of the potters’ livelihoods.

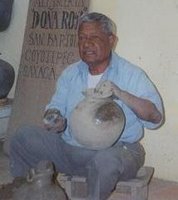

Rosa’s son gave us a demonstration of the making of the pottery. He did no use a wheel, but only his hands to get the clay close to the shape and size he wished. He uses a few tools, handmade from gourds and bamboo, to shape the pottery piece more perfectly. Then it is wrapped in plastic and put in a dark place to begin the drying process. After three days it is

taken back out and a mouth or neck is added.

taken back out and a mouth or neck is added. or a knife is used to cut out patterns. Then the pot is rubbed firmly with the quartz rock, and the pressure causes the surface to become shiny.

or a knife is used to cut out patterns. Then the pot is rubbed firmly with the quartz rock, and the pressure causes the surface to become shiny.Now they make all kinds of the black pottery in every size and shape imaginable, from large pots, to tiny detailed vases, to adorable animal figurines.